Researchers have discovered and deciphered a language lost for thousands of years by studying two ancient clay tablets that compare to Rosetta Stone.

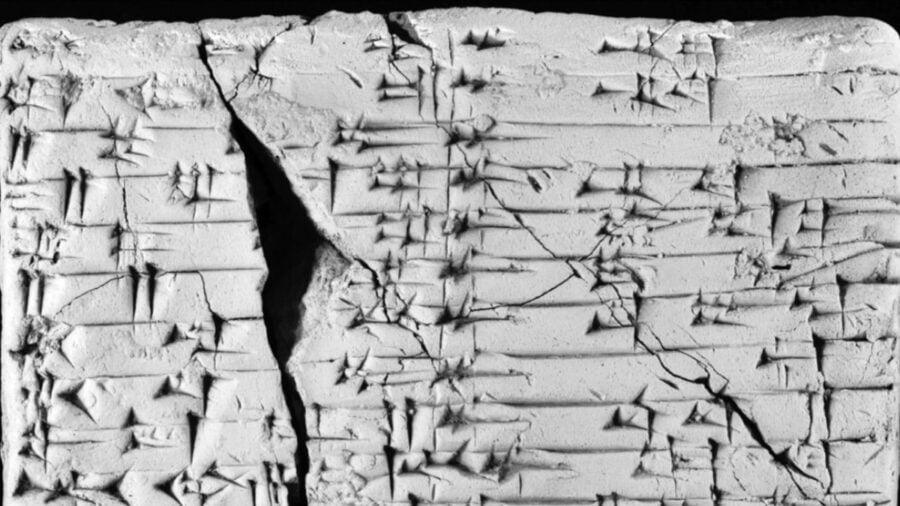

The tablets, which are believed to be 4 thousand years old, were found several decades ago in Iraq. They were kept in separate collections: one in the Jonathan and Jeanette Rosen Cuneiform Collection, and the other in a private collection in London.

Both tablets are written in the landscape format usually associated with Middle Babylonian Tablets dating to the Kassite period of the first millennium in southern Mesopotamia.

Since 2016, researchers Manfred Krebernik and Andrew R. George have been studying the tablets. In January, they published their findings in the Revue d’assyriologie et d’archéologie orientale, or Journal of Assyriology and Oriental Archaeology.

“The text of both tablets is divided by a vertical ruling into two columns, after the manner of the lists and vocabularies that are typical of Babylonian pedagogical scholarship,” the authors write. “The right-hand columns contain text in the Old Babylonian dialect of the Akkadian language.”

On the other side, something “remarkable” was discovered – a lost language.

“It is the left-hand columns of our two tablets that yield the remarkable content,” they write. “They contain text which bears many indications of reproducing a North-West Semitic language.”

The information on the right side of the tablet is intended to translate the unknown language on the left side, the authors write.

“According to the normal practice of two-column academic lists, beginning in the early second millennium, the right-hand column should explain, line by line, the material in the left-hand column,” the authors wrote.

After analyzing the words and sentences, the researchers were able to conclude that the language of the left column was probably a lost Amorite language, and the right column was its Akkadian equivalent. The Amorite language is the predecessor of Hebrew, and until now we knew only a few nouns from it. The information contained on the tablets overturns this perception.

“Our knowledge of Amorite was so pitiful that some experts doubted whether there was such a language at all,” the researchers said in an interview to Live Science. But “the tablets settle that question by showing the language to be coherently and predictably articulated, and fully distinct from Akkadian.”

The tablets also provide insight into Amorite communities and beliefs. One of the fragments of the tablet consists of the names of gods.

In addition to their format and similarities to language study guides, the two tablets have other interesting features in common.

“The singularity of the two tablets’ content may indicate that they come from the same scriptorium,” the authors wrote. “They are sufficiently similar in handwriting to suggest that they may even be the work of the same individual scribe.”

A potential criticism of the study is that the researchers primarily relied on photographs of the tablets, as both are part of private collections. Still, both Krebernik and George believe the study’s findings were important to publish.

Loading comments …